This blog is about removing redundant web content from a large site.

Before I start, I should say that a much more sensible person would have got an agency to do this. At several points during the process (which I started in October) I’ve thought I was being far too stubbornly INTJ about the whole thing and it would be easier to hand it over to a bigger team of people who could work on it full-time. But it was interesting and technically achievable – I’ve come to realise I can’t say no to anything that can be described like that.

What were the issues?

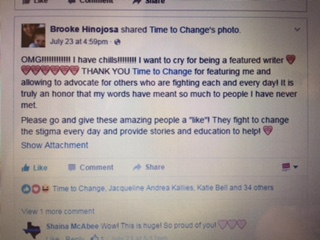

During my first year at Time to Change I’d slowly been discovering a lot of redundant content. A lot of it was unnavigable, which I think was part of the problem – whoever created it had left, forgotten it was there or for whatever reason abandoned it to float around the website without its parents. It happens in any organisation, perhaps particularly in busy charities where everyone’s working at such breakneck speed that the phrase “just get it up there and we’ll deal with it later” can become common by necessity.

The tricky thing is that nobody does deal with it later, because we’re all straight on with the next cripplingly urgent thing. And so it continues until there are are over 5,000 out of date pages that no-one but Google has time to notice.

A crucial part of this was that we didn’t have a system for forcing parent page assignation, so bypassing this step and saving everything as a page in its own soon-to-be-forgotten-about right became inevitably common practice overtime.

A further contributor to the problem was that we had no processes in place to deal with content that had a known shelf-life, so community event listings from 2011 continued to sit there gathering dust in the absence of an agreed way of unpublishing and redirecting them.

How did we address these?

As well as dealing with the content that needed to be removed, I’ve been keen to make sure we improved our set-up to negate the need for such a time-consuming audit in the future. With a bit of development, now when people add content to the site they’re asked to assign a parent by default, and an auto-generated url now inherits that breadcrumb trail as standard.

To deal with the event listings, I’d hoped for a module that would manage these automatically based on a set expiry date, but the slightly more laborious alternative of manually setting an auto-unpublish date when approving the listing and then using Siteimprove to pick up the 404 for redirecting is a fine substitute.

Incidentally, Siteimprove has also been great for us in a number of other ways, and I found you can haggle them down fairly substantially from their opening service offer, I’d definitely recommend them.

How did we ascertain the redundant content?

Although we can export all pages on the site from our CMS, I wanted to make sure we knew which were the high performers so we were making removal decisions within an informed SEO context. With that in mind, I picked the slow route of exporting them 5,000 rows at a time, in rank order, from Google Analytics.

Once I had a master spreadsheet of 17,000 pages, I looked through the first hundred or so to identify any top performers that might also fit the removal bill. Happily there weren’t any I could see that ticked both boxes – top performers were, as you’d hope, well used and positioned pages, or personal stories and news articles that remain indefinitely evergreen.

With that reassurance locked down, I could sort the spreadsheet alphabetically as a way of identifying groups of similar pages – e.g. blogs, news stories, user profiles and database records which we wouldn’t want to remove. It also identified duplicate urls and other standard traffic splitting mistakes. I then selected and extracted these from the spreadsheet, cutting the master down to around 10,000 pages.

Next I wanted to filter out the dead links, because we now had Siteimprove to pick these up and a weekly digital team process of redirecting highlighted 404s crawled by the software, so they didn’t need to be included in the audit.

As GA exports urls un-hyperlinked and minus the domain, I needed to add these in. I used the =concatenate formula to apply the domain and the =hyperlink formula to get them ready to be tested. I then downloaded a free PowerUps trial and ran the =pwrisbrokenurl dead link test for a couple of days over the Christmas holidays. It’s worth saying my standard 8gb laptop struggled a bit with this, so if you have something with better performance, definitely use that.

PowerUps divided my data into broken and live links so I could filter out the broken ones and be left with an updated master spreadsheet of every page that needed auditing by the team. There were just over 6,000, which we divided between us and checked on and off over several weeks, marking them as either ‘keep’ or ‘delete’ and fixing the url structures and parent assignation as we went.

That process identified 1,000 relevant and valuable pages to keep, and 5,000 redundant, out-of-date and trivial ones to remove. Past event listings make up a large proportion of these, but I’d also say you’d be surprised how many other strange things you find when you do something like this!

What’s next?

Now we know what we’re removing, I’m going to get a temp to unpublish and redirect it all, which I hope will take about a week. From there I’m going to look into how we might go about permanently deleting some of the unpublished content, as a spring gift to our long-suffering server.

Once that’s done we can move onto the content we’re keeping, so the next phase of the audit will be about ensuring everything left behind is as fit for purpose as we can make it – I expect this to go on until the end of the quarter.

That time should start to give us an indication of Google’s response to the removal of so many pages. I’m a bit nervous about this and prepared for an initial dip in traffic, but by Google’s own standards I’m hoping for a curve that looks a bit like this:

I’ll keep you posted!